Introduction

About the data sharing playbook

The Office of Policy and Management (OPM) noted in its Legal Issues in Interagency Data Sharing Report that leveraging data from multiple state agencies can improve program administration, policy analysis, research, and performance management.

In this playbook, we lay out strategies that will help Connecticut state agencies share data safely, securely, and ethically. The strategies are based on best practices from other states, specific examples and methods from Connecticut state agencies, and the recommendations found in OPM’s report. The strategies are focused on interagency data sharing, although many practices will also benefit sharing data with the public.

Note that this playbook is a work in progress and does not represent official IT or technology policy for Connecticut. We will be adding more content and updating the playbook over the coming months.

How to use this playbook

We recommend that agencies who own data read the following sections in order to build a data sharing framework that respects the laws and regulations that apply to their data:

Agencies that seek to request data will benefit from the following sections to initiate strong data sharing partnerships:

Finally, we recommend that both parties read the guidance on transferring data before transferring data to preserve the confidentiality and integrity of the data being shared.

Methodology

The guidance in this playbook is the culmination of a 4-month research initiative conducted by OPM, OEC, and Skylight Digital, a digital consultancy for government.

Our research involved:

- User interviews with 13 data sharing practitioners across Connecticut state agencies

- Research into best practices from data sharing experts

- Research into case studies from other states

- A detailed technology tool review to document the secure channels for data transfer available to Connecticut state agencies

- Findings from OPM’s Legal Issues in Interagency Data Sharing Report

Enabling Data Sharing

Identify who plays each data-related role.

Identifying who plays each data-related role allows organizations to establish who has the responsibility of fielding external inquiries, designing sharing procedures, and executing requests. The first step in setting up a strong data governance model and maintaining institutional knowledge of the data sharing process is to establish and communicate these roles.

Although the roles below are described separately, the same person may exercise more than one role and may have a separate job title and function. For example, a single contractor may act as both the steward and custodian for the agency’s data. In small agencies, the data officer may also fulfill the data owner, custodian, and steward roles. The important takeaway is that agency leadership and the team need to know who’s the go-to for each set of responsibilities in the data system.

Agency data officer

Agency data officers serve as the main contact person for inquiries, requests, or concerns regarding access to the data of an agency. The agency data officer, in consultation with the Chief Data Officer and the executive agency head, establishes procedures to ensure that the agency complies with requests for data in an appropriate and prompt manner. 1

The role of agency data officer was established in Connecticut by Public Act 18-175, which required executive branch agencies to designate an employee to serve as the primary contact for inquiries, requests, and concerns about access to data at their agency, and to be responsible for implementing the provisions of P.A. 18-175. See the list of agency data officers.

Data owner

The data owner is accountable for the quality and security of the data and holds the decision-making authority about data within their domain. The data owner varies by dataset, and there may be multiple data owners. For some datasets, a data officer is the data owner, and in others, it may be the program lead.

Data steward

The data steward is responsible for the governance of data and ensures the fitness of content and metadata. Stewards exercise established processes, policies, guidance, compliance, and rules in this effort. They are usually the subject matter experts and data analysts that work with the data on a daily basis.

Data custodian

A data custodian is responsible for the technology used to store and transport the data. The role can be filled by either a person or team, and data custodians are usually database administrators, data analysts, or software engineers.

Legal counsel

Legal counsel is a person or team that can evaluate data access and use and help craft appropriate legal agreements when needed.

Privacy and compliance officer

This person or team develops and implements policies and procedures to protect individual rights and comply with federal and state law. The privacy and compliance officer also investigates any data incidents and breaches.

Create and publish a data dictionary.

A publicly-available data dictionary helps requesters understand what data your agency collects and possesses. It can also help them craft requests that reference specific tables and fields, making the request easier to fulfill. The data dictionary should:

- Describe all of the datasets for which your agency is responsible

- Contain information on how each of the datasets was collected

- Define the individual fields in each of the datasets

- Indicate levels of access for each of the datasets, including which data is alreaddy open, which data is restricted, and which should not be used, or is not available

Document metadata.

Metadata is a set of information that describes the fields in a dataset. It provides data about your data. It includes information such as when and how the data was gathered or any other information that might describe an aspect of the data. It is important to keep detailed notes on the metadata and process by which the data was collected because this information can facilitate easier and more effective use later on.

One common misconception about metadata is that it is solely the definitions of the various fields in a dataset. However, metadata includes much more than these surface-level characteristics. Anything that gives additional information about the nature, structure, or gathering process of the dataset counts as metadata. Some examples of metadata for different types of media include:

- Photographs / images: date and time the photo was taken, who took the photo, location where the image was captured, and camera settings used to take the photo

- Books / reports / documents: title, author, publishing information, year of publication, table of contents, index, date of last update / modification, and number of pages

- Emails / communication records: person sending the communication, person receiving the communication, message text, date and time of correspondence, subject line, IP addresses of sender and responder, and encryption details

- Spreadsheets / databases: names of column fields, explanation of fields, number of users / respondents surveyed, number of missing data entries, integrity constraints, data types included in the table, and date and time the information was collected (including multiple records if gathered over a period of time)

When tracking metadata, it’s important to:

- Document as much information as you can about the higher-level aspects of a dataset: its source, update frequency, timestamps of collection, expected level of detail, explanations of tags, data quality, etc.

- Be consistent about the language you use to describe metadata

- Avoid acronyms and language that might be specific to you or your agency, since metadata can help recipients of data sharing understand what a dataset is all about

Recommended reading

- Metadata guidelines for publishers on data.ct.gov

- P20 WIN Data Dictionary

- Manually creating a data dictionary

- Smithsonian Data Management Best Practices

Update Connecticut’s High Value Data Inventory.

Connecticut’s High Value Data Inventory (Non GIS) and Connecticut’s High Value Data Inventory (GIS) are data catalogs that highlight general information about high-value datasets possessed by state agencies. The annual maintenance of the high value data inventories is required by P.A. 18-175. At the end of each year, OPM will reach out to agencies to provide updates by December 31 of that year. By keeping your agency’s datasets up to date in the catalog, you help other agencies and the public understand what data your agency owns and who to contact for more information.

To update the inventory, email both scott.gaul@ct.gov and pauline.zaldonis@ct.gov with the subject line “CT High Value Data Inventory Change Request.”

Review data for implicit biases.

As organizations become more data-driven, data experts are discovering more instances in which unaccounted biases in data perpetuate racism, sexism, and other forms of discrimination.

The data that government agencies, academic researchers, and other organizations collect most likely contain implicit biases. These biases can be introduced due to:

- Whose data is collected — Does a dataset contain a representative sample of people across different demographics and backgrounds (i.e. multiple races, ethnicities, geographic locations, ages, genders, etc.)?

- Whose data isn’t collected — Does the data leave out a specific demographic group that might not frequent the service where the data is collected?

- How the data is collected — For example, is the data collected via interview in one area and via a form somewhere else?

Consider possible sources of bias in your agency’s data carefully. If you don’t identify possible bias, communicate it to data requesters, and work to reduce it, the decisions made based on your data may have serious unintended societal implications.

Here’s an example of how implicit bias can have unintended consequences:

Researchers discovered that a major health provider’s algorithm favored white patients over black patients when deciding who would benefit from extra medical care. The researchers attributed the algorithm’s bias to the data that was used to create it. Researchers noted that the health provider attempted to prevent bias by omitting the patient’s race in the algorithm. Nevertheless, the algorithm amplified underlying inequities in access to healthcare. In the US, white patients incur more medical costs than black patients due to long-standing disparities in wealth and access to healthcare. Because of this difference in access to care, the algorithm perpetuated the disparity by determining that white patients would benefit more from extra medical care than sicker black patients. 2

Work to eliminate possible sources of bias.

Data analysts are ultimately responsible for how they use your agency’s data; however, as the data owners and experts, you can help data analysts avoid biases in data that perpetuate racism, sexism, and other forms of discrimination.

First, be open about the limitations of the agency’s data to reduce the likelihood that it will be used in ways that have unintended consequences. Second, work towards systemic changes to data collection practices. Finally, require data requesters to demonstrate responsible use of your agency’s data. The recommended reading below provides guidance on identifying and eliminating sources of implicit bias.

Recommended reading

- Algorithmic Justice League

- Confronting Structural Racism in Research and Policy Analysis, Urban Institute, 2019

- Data 4 Black Lives, MIT, 2019

- How I’m Fighting Bias in Algorithms - Joy Buolamwini, TED Talks, 2016

- Racial bias in a medical algorithm favors white patients over sicker black patients, The Washington Post, 2019

- The era of blind faith in big data must end - Cathy O’Neil, Ted Talks, 2017

- Weapons of Math Destruction, Cathy O’Neil, 2017

- When computers make biased health decisions, black patients pay the price, study says, Los Angeles Times, 2019

Develop a data request process.

A clearly documented data request process can facilitate successful requests. This section covers some of the supporting documents to develop as part of a comprehensive data request process.

Remember that the data request process must abide by the regulations and laws that apply to each dataset. For more detailed information, refer to Establish a privacy policy and the report on Legal Issues in Interagency Data Sharing, including the appendices reviewing state and federal laws and regulations.

Request form

Ensure that the data requester answers the questions below in order to evaluate the benefits and mitigate the risks of sharing data.

- What is the requester’s contact information and organization?

- What is the purpose of the request?

- How does the requester plan to use the data?

- Who will have access to the data?

- What are the specific data they are requesting, and what are the specific parameters, such as individual or aggregate data and over what time period?

- How will the data be used? What methods will be used in the analysis of the data?

- How will results be reported? With whom will they be shared? How will they be disseminated?

- How frequently will this data be needed? For example, is this a one-time need or a recurring need?

- How long is the requester seeking to keep the data? When and how will the data be destroyed? How is this reported or disseminated to the data owner?

Examples

Flow diagram or detailed narrative of the steps

It’s important to have a way to illustrate or describe the data sharing process from start to finish. Common approaches include using a flow diagram or descriptions for each step.

Examples

Data dictionary

A data dictionary describes the agency’s data. (See Create and publish a data dictionary.)

Examples

Data request fees

A request fee schedule communicates the cost of requesting data. Both the Department of Public Health and P20-WIN have fee schedules, but each agency may have unique procedures for enacting request fees. We recommend that you consult your agency’s legal counsel for specific guidance on fee schedules.

Examples

Footnotes

Safeguarding Data

Develop privacy and security compliance policies, standards, and controls.

Policies are high-level statements about how data should be handled, similar to a vision statement. Standards outline the rules that govern putting policies into action, and controls provide specific instructions about how to implement a standard.

In order to facilitate secure and compliant data sharing:

- Data requesters must understand the privacy and security compliance standards of the data they are requesting

- Data owners must ensure that they clearly define the privacy and security compliance standards that govern the data they own

The points below highlight how to define and understand privacy and security compliance.

Establish a privacy policy.

A privacy policy is an externally-facing document for the people from whom you might collect data. It explains how your agency uses personal information that may be collected when the public interacts with the agency. The privacy policy should include the types of information gathered, how the information is used, to whom the information is disclosed, and how the information is safeguarded.

Here are some of the questions to ask when you document a privacy policy:

- Why do we collect personal information?

- What information do we collect? (Review the data dictionary.)

- When and how do we disclose/share information?

- How do we protect personal information, including the administrative, technical, and physical strategies?

- How do we protect the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of confidential information that is created, received, maintained, or transmitted?

Document critical data elements.

Confidential Information (CI) is any non-public information pertaining to the agency’s business. Personally identifiable information (PII) is any data that can be used to identify an individual. Examples of PII include a user’s name, address, phone number, and social security number.

Data owners should also document subsets of PII, such as:

- Payment Card Industry (PCI) data — credit card information

- Protected Health Information (PHI) — information about an individual’s health

- Education records — data maintained by a school about students that includes information like test scores, special education records, courses taken, and attendance

Understand the laws that govern critical data elements.

State agencies need to understand the laws that govern each dataset based on its CI and PII. The standards and laws that govern data are critical in order to know:

- How data should be stored

- How data can be used

- What data can be shared (e.g., individual rows or aggregate totals)

- How data are transferred

- How data are disposed of

For more information about applicable federal and state laws, refer to the Legal Issues in Interagency Data Sharing report and accompanying appendices.

Recommended reading

- The Health Insurance Information Portability and Accountability Act of 1966 (HIPAA): Implications for Research with Administrative Records, Children’s Data Network at the University of Southern California, 2016

- Family Educational Rights Privacy Act of 1974 (FERPA): Implications for Research with Administrative Records, Children’s Data Network at the University of Southern California, 2016

Define acceptable use standards.

Define acceptable use standards based on the laws and regulations that govern the use of your agency’s data. These standards will help define the specific requirements in data sharing agreements for keeping data secure. For example, for sensitive data, the data owner may require that the requesting party dispose of the data after a specific amount of time.

Develop, implement, and maintain a comprehensive data-security program.

Your agency will need legal assistance creating a comprehensive data-security program that adequately protects CI. The program will need to be consistent with and comply with all applicable federal and state laws and written policies related to protecting CI.

The data-security program should cover considerations like:

- A security policy for employees related to the storage, access, and transportation of data containing confidential information

- Reasonable restrictions on access to records containing confidential information, including access to any locked storage where such records are kept

- A process for reviewing policies and security measures at least annually

- The creation of secure access controls to confidential information, including but not limited to passwords

- Encryption of confidential information that is stored on laptops or portable devices or that is being transmitted electronically

Enforce compliance controls.

A control is a safeguard to avoid, detect, or minimize security risks that might compromise the confidentiality, integrity, and accessibility of data. For example, a data owner might require a quarterly review of all users with access to a database or that people working with the data undergo compliance training.

Responding to Data Requests

Having an established protocol for responding to a request for data will save you time and effort (see Develop a data request process). The following suggestions will help you respond smoothly to different types of requests.

Ask key questions up front.

Establish a process for how key questions are asked, answered, and documented. We’ve included a detailed list of questions to ask in the section on developing a request process, including:

- What is the purpose of the request?

- How does the requester plan to use the data?

- Who will have access to the data?

- What is the specific data they are requesting and what are the specific parameters?

If the requester is planning to combine data with another dataset, this will require careful review and consideration from both teams. This could be a complex process, and we’ve included some discussion of data linking in Appendix C.

Identify the type of legal data sharing agreement you will need.

Legal counsel should advise you on the specific type of legal agreement needed to share data. However, the information below can help frame productive conversations with your data-sharing partners.

The type of agreement you will need depends on factors like:

- Whether the data contains personally identifiable information (PII)

- The sensitivity of the data requested

- The type of organization requesting the data

- How the data will be used

- The scope and duration of the request

There are multiple types of data sharing mechanisms available to state agencies. Each of them is governed by unique requirements and legal considerations.

But first: Do you even need an agreement?

Sharing data that is open to the public does not require an agreement. If the requesting party doesn’t need to identify specific individuals, it may be preferable to release the data to the public by publishing it on data.ct.gov.

Common types of agreements

The following section provides a brief description of these common types of agreement and when to use them:

- Memorandum of Understanding (MOU)

- Data Use Agreement (DUA)

- Enterprise Memorandum of Understanding (E-MOU)

- Data Sharing Agreement (DSA)

- Business Associate Agreement (BAA)

- Statement of Work (SOW)

- Non-Disclosure Agreement (NDA)

While each of these agreements has a specific function (and a context in which it is appropriate to use), it is not necessarily the case that an agency looking to share data can solely choose any one of these agreements and move forward. These agreements often work together to provide the full details of the nature of a data sharing agreement (for example, the E-MOU, DSA, and DUA tend to work together rather than operating alone).

Memorandum of Understanding (MOU)

MOUs are best suited for ongoing data transfers that have consistent and formalized parameters. An MOU:

- Identifies the roles and responsibilities of the involved groups

- Describes why an agreement is required

- Specifies the terms and conditions for the partnership

MOUs are especially important when the basis for a data sharing relationship is grant funding or a service contract. The process of establishing an “MOU enables potential partners to identify similarities and differences in their priorities and goals, available resources (time, money, and expertise), project timelines, and expected outcomes prior to collaboration.”1

Data Use Agreement (DUA) or Data Use Licenses (DUL)

Data Use Agreements (DUAs) or Data Use Licenses (DULs) are best suited for individual data sharing transactions. DUAs precisely specify the parameters for the data transfer, who will have access to the data, the intended use of the data, and how the requester should destroy data.

They may also “include specific time parameters for data use or provide special provisions for data disclosure or requirements for the data holding agency to review resulting research before its publication.”2

Enterprise Memorandum of Understanding (E-MOU)

An E-MOU is a long-term agreement signed by multiple parties in order to facilitate multiple and diverse data sharing requests. E-MOUs usually:

- Describe involved parties

- Set up governance boards

- Define codified request procedures

- Highlight the rights and responsibilities of data stewards and requesters

E-MOUs are mostly used to facilitate government agency to government agency data sharing and have been implemented in multiple states.3

Data Sharing Agreement (DSA)

Data Sharing Agreements are best suited for establishing long-term data sharing relationships that involve multiple transfers with different parameters. Data Sharing Agreements identify the involved parties and the terms and conditions for the partnership. They can stand independently or be an addendum to an MOU or E-MOU.

Since it defines an ongoing relationship for multiple transfers, a DSA may also define a process for authorizing data requests along with requirements for storing, protecting, and disposing of shared data.

Business Associate Agreement (BAA)

A Business Associate Agreement is a written arrangement that specifies each party’s responsibilities when it comes to PHI (personal health information). HIPAA requires covered entities to only work with business associates who assure complete protection of PHI.

Statement of Work

The statement of work is a detailed overview of the project in all its dimensions. It’s also a way to share what the project entails with those who are working on the project, whether they are collaborating or contracted to work on the project. This includes vendors and contractors who are bidding to work on the project.

Non-Disclosure Agreement (NDA)

A non-disclosure agreement is a binding contract between two or more parties that prevents sensitive information from being shared with any others.

Types of data sharing relationships

Below is a list of data sharing relationship types along with guidance on the types of agreements that might best facilitate data sharing. We will cover data sharing from:

- Government organization to government organization

- Government to external company

- Government to the public

Government organization to other government organizations (Interagency data sharing)

Connecticut state government agencies depend heavily on MOUs for data sharing. However, the Office of Policy and Management (OPM) recommends that agencies develop more flexible, durable agreements by:

- Signing a policy agreement among the participating agency leaders to achieve an integrated data sharing process.

- Setting up an Enterprise Memorandum of Understanding (E-MOU) to avoid drafting individual MOUs for data sharing purposes.

- Using Data Sharing Agreements (DSAs) to establish individual data sharing relationships between specific data providers and requesters.

- Creating Data Use Agreements (DUAs) for individual data sharing transactions.

For more guidance on OPM’s recommendations, see the Legal Issues in Interagency Data Sharing Report.

Government to external company

Data sharing between a government organization occurs when a government organization:

- Contracts an external company to process data for its operations

- Contracts an external company to collect data on its behalf

In these cases, the SOW contract, BAA, or MOU forces the contractor to abide by the same privacy and legal responsibilities as a government organization. When designing these agreements, government agencies should take special care to establish themselves as the data owners and the contractors as data stewards and custodians.

Government to the public

Releasing data to the public does not require a special agreement. However, it does require that the government organization:

- Aggregate or anonymize the data to prevent misuse. For an example, see the public data on Connecticut’s Open Data Portal.

- If the agency determines the data must be anonymized or aggregated, they should follow cell suppression techniques outlined on the Connecticut Agency Guidance Portal. Cell suppression is an important means of masking attributes of personally identifying or protected health information that could become damaging to an individual if the data were used (possibly in combination with other datasets) to identify them.

- Follow all relevant laws or prior agreements for the release of private information. For an example, check out the Department of Justice’s Public Records.

Footnotes

Preparing a Successful Data Request

The steps below are best practices for making data requests. Data owners are frequently overburdened with daily operations. You can make it as easy as possible for them to fulfill your request by planning carefully and addressing all of the relevant questions up front.

Design questions that can be answered with data.

Before you can make an effective data request, you need to know exactly what you are looking for and why. Below are some questions to answer before moving forward.

“What is the overarching goal or objective that I want to accomplish?”

Knowing what you want before turning to data is a prerequisite to effective data use. For tips on writing goals and objectives that map clearly to specific types of data, see Appendix A: Setting SMART goals.

“What do I want to find out or measure?”

If you are conducting an experiment, then the data might be response statistics. If you are looking through financial or budgetary data, it might be spending trends, projections, and forecasts. Other situations will call for other kinds of measurements, but thinking about what you expect to find — or even the kind of answer you are looking for — will help you identify the most relevant metrics. Some examples of suitable research questions for your data include:

- To what extent is the service provided by [Program X] reaching constituents?

- Do budget allocations meet needs? Are budget allocations used by the populations in need?

- How has enrollment in [Program X] changed over the last five years?

- How did [Event X] impact residents of Connecticut?

- What is the supportive and constructive feedback of our constituents?

“How much data do I actually need?”

In the age of “big data” it may be tempting to collect as much information as possible and sort through it later. But this approach is counterproductive. Looking at too many metrics may overwhelm the analysis or distract you with red herrings that don’t actually address your question. And requesting more data than you need from a sister agency would make responding to your request more time consuming. Some suggested methods of reducing the data you have to sift through include:

- Looking at data over a smaller time frame than the whole length you want to study. Looking at smaller windows can provide clues about how better to dissect the bigger picture without having to sort through as much information.

- Identify the information you need for your data analysis. You don’t have to use every field in a dataset to answer your question. That’s why it’s imperative to know what you’d like to measure so that you can decide which fields are likely to contain relevant information.

- Build some redundancy into the data you request. Once you’ve identified the information you need, consider how you will work around a record that’s missing data in a field. Are there other fields you could use as a proxy? Add these fields to your request.

- Use derived statistics whenever possible. If you know what question you’d like to answer, then you should be able to define specific stats that provide an answer. Using a limited selection of fields, you can compute averages, differences, percentages, and other derived statistics that construct these measurements out of less data while still answering your question.

“How can I break my analysis into steps?”

Solving a series of subproblems is almost always easier than solving a whole problem at once, and data analysis is no different. Can you segment your problem into smaller steps and use different facets of the data to answer sub-questions?

In particular, what’s a good “first step” to tell quickly whether or not you are on the right track? (This is called “failing fast,” which is a good practice to save time and energy by weeding out solutions that won’t be productive.)

Identify the data.

- Before you can request data, you will need to identify the agency and program that’s likely to have the data you are looking for. This data may be found in Connecticut’s High Value Data Inventory (Non GIS) or Connecticut’s High Value Data Inventory (GIS).

- Search for any public data dictionaries or reports that can tell you what data is available.

- Find the data owner for the agency or program if it’s not listed in Connecticut’s High Value Data Inventory (Non GIS) or Connecticut’s High Value Data Inventory (GIS). One way to connect to a data owner may be to reach out to the Agency Data Officer at the agency that maintains the data you need.

Once you’ve identified the data source, reach out for any standardized processes the agency may have for making data requests. Each agency will have their own process.

Establish credibility.

Data owners are accountable for the proper use and security of their data. In order to evaluate the risks and benefits of sharing data, they will require an explanation of how you plan to protect and use it. The data owner’s agency will have its privacy and security processes, and your practices will need to comply with them. When requesting data, you should be prepared to explain:

- What your objective is (i.e. the question you would like to answer)

- How a partnership with the sister agency can you help answer that question, and how that question is a shared inquiry for both agencies

- What data you need to study your objective (including as much specific discussion of the fields of interest as possible)

- How you will account for potential sources of implicit bias in the data you are requesting. See Review data for implicit biases for more information.

- Why you need that data and what you hope to gain or analyze from the data

- Who will have access to the data if you receive it

- How you will ensure that the data is handled ethically, safely, and securely, particularly in reference to the sister agency’s data practices

- The timeline with which you hope to answer the question and analyze the data

- How communication between your agency and your partner agency will take place (should there be weekly check-ins about the data usage? Reports filed about data activity? etc.)

Recommended reading

- Getting Organized: Steps to Take before Negotiating – National Neighborhood Indicators Partnership

- Safeguarding Data: Develop privacy and security compliance policies, standards, and controls

- DATA SYSTEM: Privacy and Security from the National Neighborhood Indicators Partnership

- Legal Issues in Interagency Data Sharing Report

- Safeguarding Data: Understand the laws that govern these critical data elements

Make the case for data sharing.

An effective data request starts with a clear description of why the requested data is important to both parties’ missions and what you plan to achieve with the data. Understand the data owner’s possible motivation to take on the data sharing project:

- Will this request improve services or data quality for the partner?

- How will residents or staff be better served?

To ensure full and sustained participation, each party involved in the data sharing effort should be able to see direct benefits from their involvement.

It may also help to think about how you will respond if your first request is denied. Here are some common reasons data providers deny requests according to the National Neighborhood Indicators Partnership:

- “Preparing the file will burden our already-overworked staff.”

- “I’m afraid of being burned by bad publicity.”

- “I’m worried about mishandling or improper release of the data.”

- “The data are a mess.”

Recommended reading

- Why Data Providers Say No…And Why They Should Say Yes – National Neighborhood Indicators Partnership

Specify the parameters of the request.

The data owner needs to understand exactly how to fulfill the request. Some useful parameters or filters to consider include:

- The date range

- Specific fields or columns

- Specific datasets or databases

- Filters such as age, people tied to a specific program, or geography

Keep the scope and timeframe realistic.

Ensure that the data owner can fulfill the data request in a reasonable timeframe and with their available resources. If a data request is too taxing on the data owner, they may reject the request until the parameters change or the requester offers additional resources. Consider the time required for crafting and signing a data sharing agreement.

Transferring Data

De-identify data as needed.

Depending on the data request, the data owner may need to de-identify data in order to protect the privacy and rights of the individuals represented in the data. There are a number of ways to de-identify data, and these are summarized below.

Removing PII and confidential data

One way to de-identify data is to remove all of the fields that could be used to identify a specific individual from the data. Examples include names, phone numbers, and birthdays. (For more information about confidential data, see the section Document critical data elements.)

Aggregating data

Data owners can also choose to aggregate data. This is accomplished by providing counts of specific fields for a dataset. For example, sensitive fields like birthday and address can be converted to age range and zip code in order to provide the counts of each age group living in a specific area.

When aggregating data, it’s important to ensure that groups aren’t split up so much that it’s still possible to identify individuals. For example, if you’re aggregating based on school, test scores, grade, and race and ethnicity, the counts can’t be small enough for someone to identify individual students.

Recommended reading

- Connecticut Data Aggregation Guidance

- FERPA Data Suppression Guidelines

- Guidance Regarding Methods for De-identification of Protected Health Information in Accordance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) Privacy Rule

- Guidelines for Data De-Identification or Anonymization

- De-Identification of Personal Information

- Guide to Basic Data Anonymization Techniques

Choose the right method for transferring data.

Once the parties have agreed to share data, it’s time to consider the logistics of transferring the data. The method will vary based on the sensitivity of the data.

Open and public data

Data that is open to the public doesn’t require a secure channel for data transfer. Some options that might be suited for file transfers are:

| Technology | File size limits | Usage notes |

|---|---|---|

| Email (ct.gov and po.state.ct.us) | 20MB, 35MB | 35MB but depends on the recipients size limit also, they could have a 20MB limit. |

| Microsoft Office 360 OneDrive (ct.gov and po.state.ct.us) | 100GB | |

| Approved external device | varies | Ask IT department for more information |

| Shared network drive | varies | Ask IT department for more information |

Non-public data

All data that isn’t open to the public should be transferred through secure channels. These data include data governed by HIPAA, FERPA, or state laws and data that are confidential, subject to misuse, or simply not authorized for public consumption due to outstanding approval.

Failure to transfer non-public data securely may result in harm to citizens, lawsuits filed against the responsible government office, and severe professional consequences for the offending employee. It’s important to pay careful attention when sharing non-public data. Secure channels include:

| Technology | File size limits | Usage notes |

|---|---|---|

| Government-approved SFTP service |

|

|

| Government-approved Encrypted External Drive | varies |

|

Zipping and encryption

To accelerate secure data transfer, zip and encrypt data files before initiating a data transfer.

To zip a file:

- Right-click on file or folder

- Navigate to “Send to” option

- Click on “Compressed (zipped) folder”

To encrypt a file:

- Right-click on the zipped folder and open Properties.

- Under the General tab, click Advanced.

- Check the “Encrypt contents to secure data” box.

Enterprise Secure File Transport Services

Overview from BEST

DAS/BEST is pleased to offer Executive Branch state agencies our Enterprise Secure File Transport (SFT) Service for agencies that need to share sensitive content between other agencies, or business partners in a secure manner. This service offers the following:

- Powered by the Axway Secure Transport solution, an industry leader in managed file transport solutions.

- Provides for the exchange of file based content that ensures protection and encryption in transit and at rest.

- Meets the federal government’s strict security compliance requirements,

- Supports the use of a web-based file management environment as well as traditional secure file transport clients (e.g., FileZilla),

- Is part of the state’s data center ecosystem, providing a secure and highly available environment.

- Leverages the data center’s virtualization and storage services to further enhance reliability.

- Is available 24 X 7 X 365, including critical incident response.

- Customer support is available from 8:00 AM to 4:00 PM, Monday through Friday.

Conditions of Use:

Use of our Enterprise Secure File Transport Service has the following conditions:

- Each agency who has enrolled in this service will need to appoint a primary and alternate SFT Liaison, with whom we will work on matters associated with your agency’s use of this system. The SFT Liaison will be granted an elevated level of permissions to provide basic support to your agency (e.g., password resets, etc.)

- Content on the SFT environment is considered transitional and is automatically purged after 60 days.

See Appendix B for a step by step guide to using SFTP.

Appendix A: Setting SMART Goals

Data can help you track progress toward agency goals. The SMART methodology is an excellent strategy for connecting what you want to accomplish to the data that will indicate whether you are headed in the right direction.

Goals are SMART when they are:

- Specific — You’ve stated exactly what you want to achieve

- Measurable — You have a way to know if you are making progress

- Attainable — You have resources and a strategy

- Realistic — You’ve taken into account other commitments

- Time-bound — You have a timeframe for achieving what you’ve set out to do

Let’s say that your agency operates a help line, and the manager regularly receives complaints that constituents are waiting on hold for too long.

Here’s what a SMART goal might look like: We will decrease the average on-hold wait time from 2 minutes to 1 minute by the end of 2020.

Based on this, it’s easy to determine what data you will need:

- Current average on-hold wait time

- Average on-hold wait time between now and the end of 2020

While this is a simple example, the same principles can be applied to larger goals: take the time and effort necessary to make them specific, measurable, attainable, realistic, and time-bound.

Recommended reading

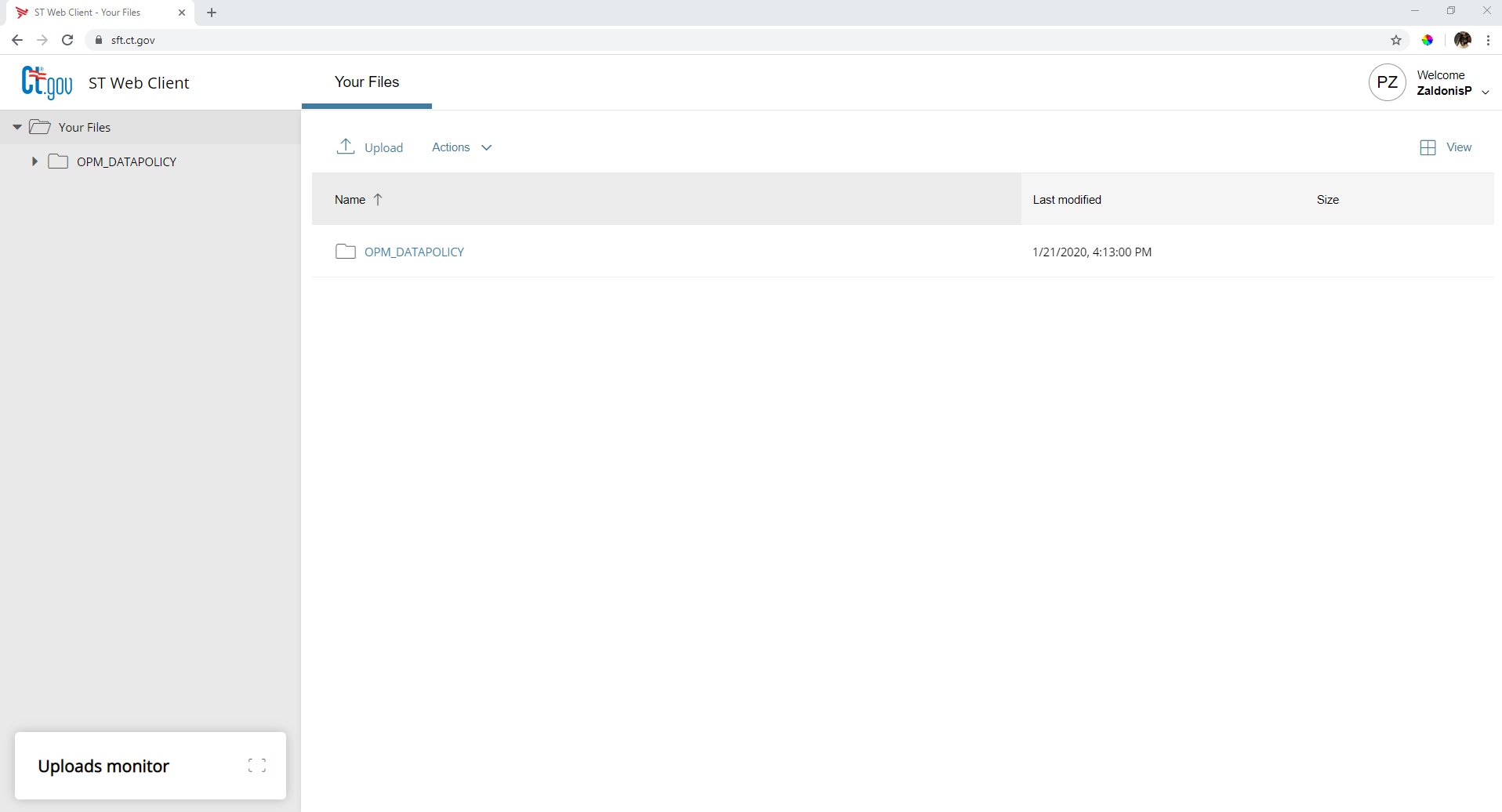

Appendix B: Steps to Use SFTP to Securely Transfer Files

DAS/BEST offers an Enterprise Secure File Transport (SFT) Service for executive branch agencies, as described in the Transferring Data section. The SFT service can be used to securely transfer data between state agencies, or other business partners, in a secure manner. The steps for using the SFT service to transfer data are described below.

-

Identify the SFT Liaison at your agency. SFTP service is available to the executive branch, constitutional offices, and quasi-public agencies and their business partners. Agencies who have enrolled in the service should have appointed an SFT Liaison, who is responsible for administering the SFT service at each agency. If you are not sure who the SFT Liaison is at your agency, your IT office might be able to help find them.

-

Ask your SFT Liaison to set you up with SFTP access. They should be able to grant you access and tell you how to log on. Your username and password should be the same as the ones you use to log into Windows, but you should confirm this with your SFT Liaison.

-

Log into the SFTP site. Once your account has been set up, go to https://sft.ct.gov and log in. Be aware that the username and password are case sensitive.

-

Work with your SFT Liaison to set up folders to organize the files you wish to transfer. The SFT Liaison can set up folders for specific data transfers, and then grant access to the desired folders to the recipient of your data transfer.

-

Make sure the person you want to share data with also has SFTP access. If the person with whom you want to share data is at another Connecticut state agency, their SFT Liaison must grant them access to the SFTP site. Once they have access, your SFT Liaison should be able to give them access to the folder with the files you wish to share. Your SFT Liaison should also be able to help you share files with a partner outside of state government.

-

Ask your SFT Liaison to give the data recipient access to the folder on the SFTP site where your data is saved. Once you both have access to the shared folder, you should be able to use that folder to transfer files.

-

Upload the data that you want to share into the designated folder. Click the “Upload” button and select the file that you want to share. The person you want to share data with should also now have access to the file via your shared folder.

-

If you have difficulties using the SFTP site, ask your SFT Liaison for help, or call DAS/BEST at 860-622-2300 and select Option 9.

Appendix C: Linking Datasets

Data linking or data matching is the process of combining two or more datasets. It allows program administrations to provide more integrated and client-friendly government services.

Data linking also provides policy analysts and researchers a wider lens to draw insights and improve services. There are two ways to link datasets — deterministic and probabilistic.

Deterministic data linking

Deterministic data linking combines individual records only if the fields that are being compared match exactly. For example, two agencies could use social security numbers to combine their datasets. This type of data linking is most suitable when both datasets have a consistent, unique identifier.

Probabilistic data linking

Probabilistic data linking combines individual records using a special algorithm that compares multiple fields to determine if two records are the same entity. For example, P20 WIN’s data linking process uses identifiers such as name, birthday, and other fields present in both datasets to combine datasets. Probabilistic data linking is best suited for datasets that don’t have a unique identifier. It’s also best suited when two datasets have a unique identifier that’s inconsistently present or untrusted.

Blocking

When comparing two datasets, checking every single possible pair is computationally taxing. For example, two datasets each containing 100 records would require 10,000 pairwise comparisons. This computational reality quickly becomes unmanageable when linking larger administrative datasets.

Blocking solves this computational challenge by only comparing pairs that are likely to match according to particular fields. For example, by using age for blocking, only records with the same birth year are compared to each other. A common strategy is to run mulitple block passes because some fields are missing or erroneous. The Australian Government’s Open Data Toolkit provides a table of fields to consider when blocking.

Measuring Accuracy

There are two types of matching errors that arise when linking records. The first is a false negative, which implies two records that fail to meet the set matching criteria actually are a match. The second is a false positive, which is when two records meet the set matching criteria when they are in fact not a match. There is a tradeoff between false negatives and false positives when determining the stringency of any matching criteria. A stricter matching criteria will decrease the number of false positives but increase the number of false negatives, while a more lenient matching criteria will increase the number of false positives but decrease the number of false negatives. The context of the data match provides guidance on which type of error to minimize.

It is very difficult to capture the true number of false negatives and false positives in a data merge. Researchers have implemented creatives methods for assessing the accuracy of record linkage algorithms. For example, researchers at the University of Michigan tested a supervised learning, record linkage algorithm by training it on a large, novel dataset that includes biometric identifiers (fingerprints) to construct unbiased measures of error. Other researchers have examined the performance of widely-used record linking algorithms with hand-linked datasets and synthetic datasets. Synthetic datasets have known errors introduced to fields of interest.

Recommended reading

- Two Methods Of Linking: Probabilistic And Deterministic Record-linkage Methods

- Linkage Feasibility—To Link or Not To Link

- Data Matching Software Tools

- Improving deduplication of identities

- Linking Administrative Data: Strategies and Methods

- Challenges in administrative data linkage for research

Active Research and Development

- Modernizing Person-Level Entity Resolution with Biometrically Linked Records

- How Well Do Automated Linking Methods Perform? Lessons from U.S. Historical Data

- Record Linkage Innovations for Human Services introduces matching processes that are still largely theoretical, such as collective matching which shifts away from looking at record linkage as a strictly pairwise challenge, instead viewing the universe of records across the datasets to be linked as nodes in a graph (i.e., as a network).